by Dr. Evertt W. Huffard

by Dr. Evertt W. Huffard

We have not stopped praying for you and asking God to fill you with the knowledge of his will through all spiritual wisdom and understanding. And we pray this in order that you may live a life worthy of the Lord and may please him in every way: bearing fruit in every good work, growing in the knowledge of God, being strengthened with all power according to his glorious might so that you may have great endurance and patience, and joyfully giving thanks to the Father, who has qualified you to share in the inheritance of the saints in the kingdom of light (Colossians 1:9b-12, NIV).

It happens to leaders all the time. When leaders in a church face a crisis, all attention and energy goes into “solving” the problem as quickly as possible–only to discover that the quick fix led to even greater problems.

It happens to leaders all the time. When leaders in a church face a crisis, all attention and energy goes into “solving” the problem as quickly as possible–only to discover that the quick fix led to even greater problems.

I was an elder long enough to understand why any church leader wants to minimize the agony created by a church conflict, improper actions of a minister, or the threat of a group of members leaving the church. You would not have to look far to find churches that have suffered serious decline because they failed to see past the crisis.

As all pilots know, you continue to fly the plane while you address a crisis in flight. Otherwise, you might find a quick fix but crash the plane!

I hear in Paul’s prayer for the young church at Colossae a call for greater endurance and patience for something that will not come quickly. Waiting for the spirit to give wisdom, living a life worthy, waiting for the fruit that God provides and anticipation of an inheritance all take the long healthy view of the church. I hear him calling them to endure faithful, not find quick fixes for success. In doing so they would have reason to thank God for the victory–in his own time.

Three Principles

As a school administrator, a church leader, and a church consultant, I have found principle-centered leadership provides wisdom to create a healthy context for growth as well as for coping with challenges. Following are three principles that have served me well in approaching a church crisis.

One principle that will eventually come to leaders through years of experience is that there are no quick fixes in ministry. That’s right!

When I say this to leaders in crisis management mode they want to ignore it, and I understand why. The pain screams louder than reason. They have exhausted all their resources. Less experienced leaders may not even believe it–they still think every problem has a solution and they don’t need such pessimistic advice.

A second principle assumes that most declining churches fail to grow because they are over-managed and under-led. The systemic problem often starts in a crisis and leaders get stuck in crisis management so long that it unknowingly shapes the culture. This church culture narrows its mission to avoiding a crisis, so any crisis becomes a threat to their mission rather than an opportunity to grow spiritually. In such a church culture, trust becomes a casualty. The loss of trust among the elders, between elders and staff, or between leaders and major groups within the congregation will need to be reversed before another major crisis comes along.

People follow leaders they trust. Leaders try to manage people and situations they do not trust. Can we assume that in crisis, leaders manage and in “normal times” they lead? Really?!

The cross of Christ symbolizes the power of spiritual influence through crisis, not using power to manage a crisis. When does Paul attempt to manage problems as an apostle? If he used apostolic power, his letters would have been very short. On the contrary, he went to great pains to exercise powerful spiritual influence in times of crisis in Corinth, Ephesus, Colossae, and Rome. As in Romans, he used an extended rhetorical argument that may not be clear to everyone when he could have given specific commands as an apostle.

Consider a third principle I find extremely helpful when relationships have been broken and the perceived peace of the church is threatened: when we judge ourselves by our intentions and others by their actions, we close the door to reconciliation and resolution to the problem. I adapted this from Covey, The Speed of Trust.[2]

At the heart of almost every conflict, you will find a loss of trust somewhere–even of God. So what makes a crisis a crisis? One way you know a crisis has developed is when you see people on all sides shifting problems into personal attacks and harsh judgments.

Managing Self

Peter Steinke describes survival leaders as those who “take expedient action based on emotional pressures; play it safe for the benefit of preserving stability; use quick fixes for restoring harmony; and find scapegoats to blame, looking outside of self for rescuing.”[3]

“Survival leaders” manage the crisis, not themselves, out of the anxiety shared by the people they lead. In contrast, leaders who manage their own anxiety, says Steinke, “take thoughtful action, risk goodwill for the sake of truth, stay the course, and manage self.”[4]

Each crisis actually strengthens their spiritual influence because they witness to the power of the spirit in walking by faith.

Steinke says, “to lead means to have some command of our own anxiety and some capacity not to let other people’s anxiety contaminate us; that is, not allow their anxiety to affect our thinking, actions, and decisions.”[5]

When a leader gets in survival mode, it is so easy to slip from normal objectivity and discernment about how to take long-term steps to health. This is a good time for a church consultant to serve a valuable role in helping leaders differentiate between emotional reactions to a crisis and thoughtful spiritual responses.

We can expect spiritual leaders to have patience, kindness, gentleness, and self-control in good times and bad. The fruits of the spirit do not just happen to show up at the time of crisis. In fact, I have witnessed just the opposite. What really makes a spiritual crisis is the absence of the spirit as leaders become impatient, controlling, harsh, rigid, or unreasonable.

Strong spiritual leaders cultivate the spirit in their hearts and lives consistently–as a daily discipline–so they will be prepared for each crisis and conflict. When leaders have the ability to walk by faith in tough times, the potential for a healthy assessment of the crisis will be more likely.

Elements of a Healthy Assessment

So what are the goals of a church consultation?

Giving advice or judging would not be a good place to start. I listen and ask questions. I seek to encourage, search for clarity to the crisis, and help them discover what the next step would be to become a healthy church beyond the immediate crisis.

To do that requires an assessment of the church as a whole–a systems approach–otherwise the focus on the problem will distract leaders from leading the church. Imagine the possibility of turning a crisis into an opportunity for the church to grow and to become healthier. To do so generates new energy and hope. It is possible that conflict could be good for a congregation.

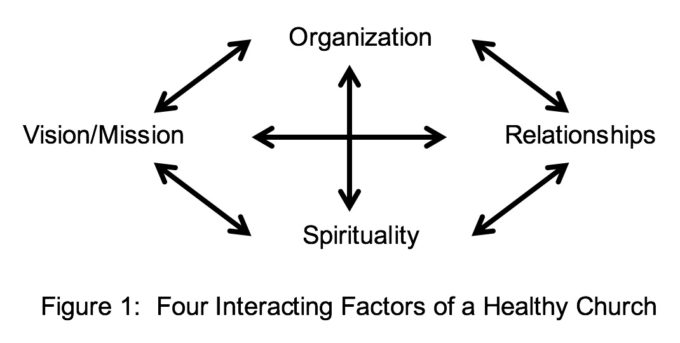

One tool I find extremely helpful in bringing clarity to assessment of a church comes from Shawchuck and Heuser. Using a systems approach in churches, they identify four factors that every healthy church needs: spirituality, mission, organization, and relationships.[6]

One tool I find extremely helpful in bringing clarity to assessment of a church comes from Shawchuck and Heuser. Using a systems approach in churches, they identify four factors that every healthy church needs: spirituality, mission, organization, and relationships.[6]

1. Spirituality: Because churches are much more than a civic group, family or tribe–spiritual realities make them what they are. Examples I look for in this area are faithfulness to God and the word; persistence to the point of making sacrifices for the sake of the kingdom; renewal when knocked down; spiritual discipline in setting priorities; high levels of trust and credibility; and fruits of the spirit.

2. Mission: This term gets entangled with “vision” so that the two will often be used interchangeably. However, because I would not use them interchangeably in the church context, both need clear definition.

God sets the vision because the kingdom belongs to him. As per Genesis 12, his vision is that the church blesses all nations through Christ. No need for long meetings and dialog for a church to come up with a “vision statement.”

It is not our church so we have no right to determine the vision. God expects every church to be a blessing. Our vision is constant and unchanging until the Lord returns.

Shawchuck and Heuser make the distinction between mission and vision by equating vision to spirituality.[7] The critical question is HOW do we get it done? The answer to that question becomes our mission. Vision is permanent and mission is adaptable.

The mission of a congregation is practical, concrete, always in process because the organization is in an environment that is always in transition–a stable, status organization is probably dead. The mission puts flesh and muscle on the vision, making it real.[8]

3. Organization: A vision needs a spiritual imagination, but a mission needs an organization to be executed. The church is the body of Christ with each member working together for a common mission. Over time a mission can be lost but energy continues to be consumed (even wasted) by an organization.

The contract becomes obvious in a crisis when the major concern is maintaining stability rather than leading a mission. These are two very different concerns. A clearly-shared mission has greater power in pulling people together. A crisis or conflict may help identify the dysfunction of the organization, such as treating symptoms as problems, bottlenecks, non-alignment, or self-defeating practices.[9] If more energy goes into maintaining the organization than the mission, something needs to change.

“Eroding human relationships are not the cause of the problems, but they are the results of inappropriate and ineffective relationships between the congregation’s mission, environment, design, and spirituality.”[10] In other words, to address internal conflict without attention to other factors will only lead to more frustration.

As illustrated in Figure 1, these four factors depend on each other to develop a healthy church. Take any one factor out of the equation and the church ceases to be what God created it to be. The size of the church also influences these factors. I have found that smaller churches struggle more with mission and organization while larger churches struggle more with spirituality and relationships.

For a small church in a crisis, the quick fix may be catering to the weakest member to keep everyone happy. In the large church, the quick fix may be organizing a new ministry with adequate communication and preparation. In these cases, the mission or relationships become the larger casualty.

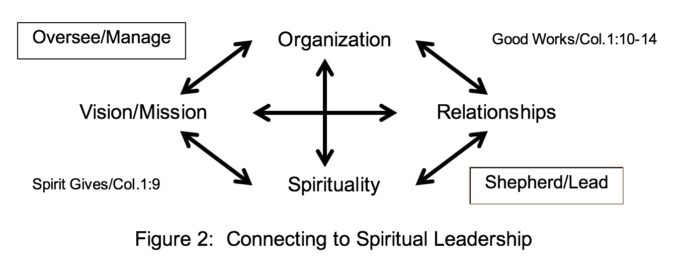

Figure 2 expands the model. The wisdom of the spirit gives the spiritual basis for mission while good works flow through organization and relationships. This system approach also illustrates the responsibility of elders to provide oversight in executing the mission and organization of the church and to provide shepherding in spirituality and relationships.

Figure 2 expands the model. The wisdom of the spirit gives the spiritual basis for mission while good works flow through organization and relationships. This system approach also illustrates the responsibility of elders to provide oversight in executing the mission and organization of the church and to provide shepherding in spirituality and relationships.

If the crisis involves all these areas, it will be vital that the leaders work well together to resolve the crisis through managing and leading. If the crisis is spiritual or relational in nature, a managerial approach would obviously not fit.

I have found that this model applies in multiple church functions and teams…to a specific ministry in crisis or to a ministry team.

Patrick Lencioni identified five dysfunctions of a team that interact with this grid. The absence of trust is a spiritual and relational issue. Fear of conflict suggests fragile relationships and lack of trust. A lack of commitment can come from an ill-defined mission or the absence of a clear, unifying mission. The avoidance of accountability is an organizational problem. Inattention to results comes as no surprise if there is neither a mission to set specific objections nor the organization to reach specific objectives.[11]

As I read Colossians 1:9-12 again, I am challenged by Paul’s tendency to raise the bar really high. I am almost frustrated by placing the bar so high! Note his references to all wisdom; praise him every way, every good work, all power, and great endurance and patience. Is he expecting too much? What happened to words like “some” or “as often as you can”? He left little room for exceptions.

Crisis or not . . . the bar is high. Maybe he knew that we all tend to rise to the level of expectation. The power of God and gifts of the spirit can equip us to transition our anxious hearts from the quest for a quick fix to a healthy church honoring God in all it does.

I have seen it happen and I praise God for his great power. I have seen several churches put tremendous pressure on leaders to quickly find a new preacher rather than allow for the year or two it might take to find the right person.

Those who were patient have reason to praise God. Those who were impatient and found a quick fix were looking for a preacher again in three years! Those who were patient to appoint shepherds when the right men were ready can praise God today for the spiritual influence they provide the church.

Dr. Evertt W. Huffard has been teaching missions and leadership at Harding School of Theology in Memphis, TN since 1987. He served as Vice President/Dean at HST from 1999-2014 and is currently Professor of Leadership and Missions at HST. The son of church planters in the Middle East, he has also served among the Arabs in Nazareth, Israel. They have also served in an urban ministry in Los Angeles, CA. In the past 20 years, he has provided leadership seminars, retreats or consulting for churches in 20 states and for mission teams all over the world. He helped initiate the Shepherd’s Network at HST to encourage and to equip church leaders. You can reach him at ehuffard@harding.edu.

[1] Peter Steinke, Congregational leadership in Anxious Times (Alban Institute, 2006), p. 101.

[2] Stephen M.R. Covey, The Speed of Trust (Free Press, 2006), p. 76.

[3] Steinke, p. 149.

[4] Steinke, p. 149.

[5] Steinke, p. xii.

[6] Norman Shawchuck and Roger Heuser, Managing the Congregation (Eerdmans, 1966), p. 46.

[7] Shawchuck and Heuser, p. 101-103.

[8] Shawchuck and Heuser, p. 101.

[9] Shawchuck and Heuser, p. 138.

[10] Shawchuck and Heuser, p. 209.

[11] Patrick Lencioni, Overcoming the Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Field Guide (Jossey-Bass, 2006), p. 6.