This is a continuation of our posts about a TED Talk. (part 1, part 2, part 3)

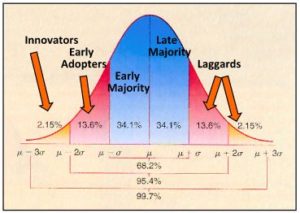

In my experience, this Bell Curve describes what we experience when dealing with change in the church. We can anticipate that half of our members will be open (to some degree) to changes in thinking or action. They need encouragement and reasons (as we will discuss below). But they are not opposed to change per se.

Of those open to change, a small sliver actually drives changes. These are the (dreaded) “change agents” who question the status quo and dare to value mission and effectiveness above tradition and comfort zones. A larger segment (the “Early Adopters”) see the need for change, are eager for change, and need only to be shown new ways of thinking and acting that are reasonable. They are not “faddists” (though they are often accused of this). Rather, they tend to focus on the future and recognize that the church needs to reinvent itself on occasion to stay current and relevant.

The largest segment of church members open to change (the “Early Majority”) don’t come to change quickly or reflexively. They demand that changes be discussed, tested, and evaluated. They want to see changes that work before embracing those changes whole-heartedly. They will tolerate some experimentation and even a certain degree of failure. But before adopting changes personally and permanently, they need good reasons and strong leadership and effective role models.

On the flip side, half of church members can be expected to offer some level of resistance to change. This segment of our churches is (by definition) more conservative and more wed to the status quo. It is not that these brothers and sisters don’t care about the church’s mission. It is, rather, that they closely identify the church’s mission with the church’s tradition—“We are what we do.” Change—threatening as it is, inevitably, to what we do—represents for these people an attack on the church’s identity and faithfulness.

Still, the majority of this other half of our congregations can be persuaded to adopt change eventually if:

- They are guided through the process by leaders who are patient, loving, and open

- The reasons and rationale for change are clearly articulated and closely tied to mission

- They see people they know and trust accepting these transitions personally and gracefully

- They are given time to shift their own thinking and actions (i.e., their own transition is not forced or hurried)

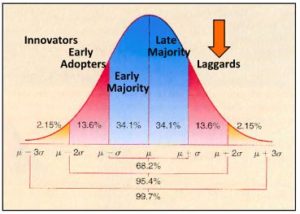

Inevitably, however, there is a segment of every church that will fight change tooth and toenail. No amount of reasoning, no amount of patience, will result in a graceful acquiescence to change. The only way change will be endured is if other options (like the rotary-dial phone) are taken off the table. Even then, some will take their rotary phones and go elsewhere. Of those who remain, we can expect a certain level of unhappiness and carping to continue with every exposure to new ways of thinking and doing.

Strategies for Change

The key to “diffusion of innovation” (according to Sinek)—the key to the adoption of changes by a population in general—is focusing on a specific “tipping point.”

That “tipping point” happens at the boundary between “Early Adopters” and the “Early Majority.” All Early Adopters require in order to embrace change are a few good reasons: “This is why you should get a cell phone” … “This is why we want to talk about the Holy Spirit.” They make changes because they want to change, they appreciate the rationale for change, they understand the connection between the proposed changes and the church’s mission.

In order for change to be adopted by a wider membership, however, more than good reasons are required. Yes, Innovators and Early Adopters have to be clear, loving, and patient advocates for change. But they also need to model those changes (and their embrace of them) in tangible, trustable, and motivating ways for those who comprise the “Early Majority.” Both logic and testimonial are needed for the Early Majority to get on board.

Once that happens, however, the rest of the church falls like dominoes. Those who belong to the “Late Majority”—though resistant to change on principle—will slowly accommodate to the new realities. Eventually, they get an email address, a cell phone, a FaceBook account. Eventually, they tolerate discussions of the Holy Spirit or a more assertive leadership role for the pulpit minister or a woman giving testimony in the assembly.

And once 85% of the church has embraced (or, at least, endured) a change in thought and action, the Laggards must decide to defer or depart.

With this “Law of Diffusion of Innovation” in mind, it is no wonder that change is so difficult in many church settings. Regardless of the issue or the process involved, we stack the deck against ourselves because we focus on the wrong audience.

Allow me to suggest that we leaders spend an inordinate amount of time focused on the Laggards among us. We are convinced we need to win over the Laggards for change to occur. And we believe that, by using our favorite tools—logic, rationale, exegesis—we can change the minds of that segment of our churches on the subject of change.

We can’t. The subject of change is not a rational subject for Laggards. It is emotional and intense and instinctive. Tradition has far more to do (for Laggards) with core issues like identity and safety than with logic and argumentation. For them, the point is not effectiveness but faithfulness. When we appeal to this segment of our churches with reasons and rationale, we only prolong the argument, deepen the divide, and make the possibility of change more remote and costly.

continued in our next article in the series

Leave a Reply